Jaguar

By J. Brun

He sat upon a gneiss rock throne. Appropriate, as his kind was deemed royalty by the Americas’ ancestors. The Aztecs believed the distinct rosettes on his fur symbolized the celestial bodies of the night sky that he ushered through the evening hours. Magic and shapeshifting, two other ancient attributes, were also present within and around him. Magic because he was surveying a land not typically associated with his kin – a saguaro cactus and mesquite tree-dominated habitat. His shapeshifting took form in my mind’s eye: he was a shadow figure in the form of a cat pushed off his perch by my two dogs only to disappear into twilight’s shadows and transform into a guttural “cough.” His vocalization represented another characteristic of his species, power, as his muscular, reverberating voice seemed to emanate from the canyon itself.

I stood across the canyon from him and held my breath. I was in awe and confused. I felt blessed but perplexed that a cat I presumed was a jungle dweller was present in my backyard desert.

Over the next decade, I learned that jaguars used to roam the Sonoran desert though their numbers were small and sparse. The big cats had been exterminated by hunters for sport and livestock reasons. Called Ohshad by the Tohono O’odham, the jaguar’s current United States detection history is exclusive to the borderlands of Arizona and New Mexico. It is a substantial restriction in territory for a cat whose ancestors crossed the Beringian land bridge into North America and called present-day states such as Washington, Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and Maryland home, as well as the Ohio and Pennsylvania river valleys.

Macho B was first documented in 1996 by lion hunters and their hounds in juniper-oak woodland. And then seen by my mutts and me three years later in Sinaloan thorn scrub habitat. Macho A was first detected by a remote game camera in 2004 under a ribbon of Sycamore trees. Two additional male jaguars were documented in the bootheel of New Mexico in 1996 and 2006, respectively. They leaped onto rock boulders and swept past scrubby juniper trees as lion hounds chased them with Warner Glenn and his camera in pursuit.

At present day, a jaguar has to pioneer a trail northward to the U.S. as most of the species are exclusive to the United States’ southern border. The jaguar is the largest wild cat in the Americas and is indigenous to diverse landscapes.

He can wander for miles vocalizing in vain for a mate in a dwindling and fragmented habitat in the Yungas forests of Argentina. She can melt into the shadows of a protected Belizean jungle preserve camouflaged by the silhouettes of strangler figs, palms, and mahogany. The endangered carnivore can hunt migrating Olive Ridley sea turtles on a moonless night along the white sands of a Costa Rican beach. The rosette cat can stalk and kill caimans in the waters of Brazil, reflecting its Tupi name, yaguareté, meaning to kill with one bite.

A female jaguar can safely swim across bodies of water like the Bavispe River in Sonora, Mexico bordering a Northern Jaguar Project preserved landscape and hear the laughter of thick-billed parrots from the higher-elevation pines. Both species are celebrated by the local community and biologists alike. Perhaps, a cub or two could follow in her aquatic wake? Meanwhile, her mate walks under that pine canopy in the Sierra Madre Occidental. The aroma of the trees’ needles diffused into the dry air with each of his silent steps.

Today, their elders and relatives could be closer to our shared Arizona, New Mexico, Sonora, and Chihuahua borderlands. A male jaguar dubbed Sombra may have dipped from the “sky islands” into a cottonwood-lined riparian corridor before venturing across sweeping grasslands to first be documented in 2016 in the Dos Cabezas mountains of southern Arizona. Before him was El Jefe, another male jaguar first chased by yet another lion hunter and his hounds in 2012, also in southern Arizona. El Jefe roamed the peaks and valleys, dry game trails, and along monsoon-flooded arroyos for a time. Then he disappeared and re-emerged years later and hundreds of miles away in Mexico in 2022. As of 2023, two male jaguars are padding along beaver-dammed streams and the lush grasslands of northern Sonora on Cuenca de los Ojos properties. Before them was Y’oko, now deceased.

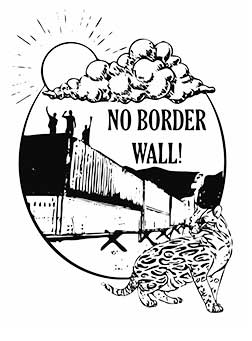

As you read these words, a jaguar could be strolling along an ancient Hohokam trading route protected by the dappled light of an oak and madrone canopy in an Arizona sky island. He (maybe she) could then follow a fellow refugee’s worn trail past the iconic saguaro cactus, the ubiquitous prickly pear cacti, or along the north-flowing San Pedro river only to stop—barricaded from their path forward—by 30-foot steel bars. Now what? Well, that’s up to us, to you.

Rise for the jaguar! Rise against border walls! Join in the jaguar’s roar for connectivity and community. Refuse to let the mythical stars of the jaguar’s lore fade to black.